I come from a time in the distant past before university fees. I was fortunate enough to attend one of the UK’s top universities without paying any fees myself. Now, in the harsh light of the year 2010, this seems like privilege beyond imagining. I certainly didn’t feel rich, I had £3,000 a year to live on (a gift form my parents since I didn’t qualify for grants) which paid for my accommodation (Class C rooms at class AA rates), my food (Tesco value range) and my books. But I left university with a degree and with no significant debt.

Right now, the average student graduating in July 2011 will find themselves with £21,198 of debt. Students graduating in 2014 may find that figure increases to £40,000 or more. And that’s based on an undergraduate degree only – not postgraduate or research work.

The rationale is that graduates will earn more and therefore will easily be able to pay of this monstrous burden of debt. Cue hollow laughter. Have you looked at the job market recently? Courses with a vocational aspect, professional accreditation or a clear path into a profession will stand students a better chance of graduating into a good job. But for most the future is bleak, especially in the arts. Unemployment is currently standing at 7.7%. For women the statistics are even worse. The number of unemployed women is at 1.02 million, the highest figure since 1988. And please note that this comes at a time when the government is introducing drastic spending cuts in the public sector, reducing Town and District Council spending by 40%. No public sector jobs for you hopefully graduates, and no civil services ones either with cuts affecting them almost as radically.

Our insect overlords seem almost surprised at the scale and scope of the student protests, as if they thought students wouldn’t notice or care about the increased fees. This morning David Willetts (the universities minister) said cheerfully patronised students: “”My real worry is that maybe young people are put off going to university because they think that somehow we are going to be charging them fees upfront. That’s not the plan… No young people or their parents are going to have to reach into their back pocket to pay to go to university. They will only pay after they have graduated. I don’t want any young person, therefore, to be worried about going to university, and some of these protests – they mustn’t put people off.”

Thanks for that, Mr Willetts, I thought it was the crippling burden of debt putting people off going to university. But now I understand those student are just confused and it’s the protests that are worrying people unnecessarily… Come off it!

And so much for widening participation. I actually found myself saying to a colleague “But doens’t the government want people form poor backgrounds without a family history of higher education to go to university… oh wait, it’s the Tories in right now.” Aimhigher, the national programme to get more working-class teenagers into English universities, will close in July 2011. David WIllets think’s it’s no longer needed and that “the universities [should] have the freedom and flexibility to decide how to spend their resources on promoting access.” Yeah, because with dwindling resources and no central support the widening participation programme will continue as vibrant as ever.

But let’s not blame the current cabinet of millionaires though. Born with a silver spoon protruding from every orifice, Cameron and co have no idea what it’s like for ‘ordinary people’ despite throwing that phrase around like a wrecking ball during the election. This is what the Conservative party is like.

I remember growing up as one of Margaret “there’s no such thing as society” Thatcher’s children. I remember the meanness, the hypocrisy and the sheer bloody-mindedness of Tory rule. And now they’re back, like the Evil Empire in act V of Star Wars, and it’s at least partly #NickClegg’sfault. (That’s the last time I ever vote Liberal.)

We should praise and support the students for marching and for protesting an unfairness that will have the worst effect on people not old enough to have voted in the last election. And, to the students, while you’re protesting don’t forget that there will be another election (however hard the Tories try to push it back into the distant mists of the future) and when there is you can march again down to your local poll station and vote them right back out where they belong.

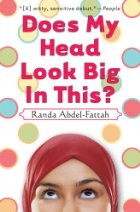

Does My Head Look Big In This? by Randa Abdel-Fattah

Does My Head Look Big In This? by Randa Abdel-Fattah