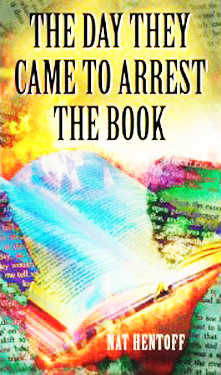

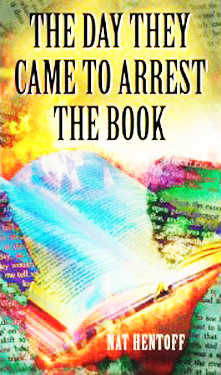

The Day They Came To Arrest the Book

September 25 to October 2 is

Banned Books Week. Here’s a list of the

top ten most challenged books in the US (in 2009) and here’s another link to the

top hundred most challenged books (2000-2009). What’s depressing about these lists for me is how

old some of these books are. We’re talking about important YA fiction that I grew up with and yet these books are still being challenged for their honest and powerful engagement with important issues.

Speak was published in 1999

The Color Purple was published in 1982

Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry was published in 1976

The Chocolate War was published in 1974

Forever was published in 1975

To Kill A Mockingbird was published in 1960

Brave New World was published in 1932

Those are books dating from 78 years ago still being challenged.

A challenge is an attempt to remove or restrict materials, based upon the objections of a person or group. A banning is the removal of those materials. Challenges do not simply involve a person expressing a point of view; rather, they are an attempt to remove material from the curriculum or library, thereby restricting the access of others. Due to the commitment of librarians, teachers, parents, students and other concerned citizens, most challenges are unsuccessful and most materials are retained in the school curriculum or library collection. (ALA)

And one has to wonder, on what basis are these challenges being made? Dr Wesley Scroggins would like to ban Speak by Laurie Halse Anderson. He cites it first in his article “Filthy books demeaning to Republic education“. Scroggins thinks this book is inappropriate and “should be classified as soft pornography”. The subject matter? A high school teenager’s struggle to speak out about having been raped by another student. I’ve read Speak several times and there is nothing in this book that could be counted as soft pornography. Perhaps Dr Scroggins equates rape with porn – in which case it’s his opinions that teenagers should be protected from.

I should also add that far from defending this book against the likes of Scroggins, Republic Superintendent Vern Minor commented: that:

“the curriculum is abstinence-based and that students can opt out of sex education classes. He also said “Slaughterhouse Five” has been removed, and that “Twenty Boy Summer” is being reviewed. Some of the issues raised by Scroggins were before the start of the school year and were complicated by the timing and renewal process of teachers’ contracts, Minor said.”

The ALA explains that challenges are often seemingly motivated by the desire to ‘protect’ children.

Often challenges are motivated by a desire to protect children from “inappropriate” sexual content or “offensive” language. The following were the top three reasons cited for challenging materials as reported to the Office of Intellectual Freedom:

- the material was considered to be “sexually explicit”

- the material contained “offensive language”

- the materials was “unsuited to any age group”

But what sort of protection are we actually taking about? Not protection from the bulling rule of a powerful clique (events portrayed in the Chocolate War), not protection from sexual abuse (events portrayed in Speak), not protection from racism (events portrayed in Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry). This so-called protection is from reading, discussing and thinking about the books which portray the issues and by-extension the issues themselves. In fact, information is being replaced by misinformation (rape = soft porn). And don’t even get me started on the value of abstinence-only sex education classes with an opt-out option – another example of misinformation or no information being considered somehow less offesnive or challenging than ACTUAL INFORMATION.

Anyway, Banned Books Week comes fast on the heels of a teenage literary festival disinviting guest of honour Ellen Hopkins after one librarian challenged the suitability of her work. When other speakers pulled out the festival was cancelled and some commenters blamned the banned author and her friends for this result. That’s right, because victims are always to blame for the acts of their oppressors.

I honestly think it’s getting harder and harder to publish important, brave and valuable books about issues that affects the lives of teenagers. Perhaps because Dr Scroggins believes all teenagers should or do live in a 1950s twilight zone world. Or perhaps because some modern publishers and critics think the issues are done and dusted: that racism, sexism, classism and other social ills are now in the past so let’s publish Disney Princesses and Glitter Fairies and forget about that difficult stuff.

Obviously there are some wonderful forward-thinking individuals in the publishing world, writers, editors, publishers and critics – not to forget the dedicated librarians who believe passionately in access to books. But I’ve been told by a prominent publisher to concentrate on the romance angle so a book of mine would be “too issuesy” and it’s common practice for every single epithet (from “fuck” to “bloody hell” to “arse”) to be stripped from my work before publication.

If it’s this difficult for parents, politicians and other ‘protectors’ of children to accept the books on the ALA list which are decades old, how less willing will they be to accept contemporary fiction with contemporary themes? There’s a bleak outlook for YA fiction if this trend continues.

But in the light of banned books week, let’s take some time to honour those authors of challenging fiction. To Judy Blume who taught my generation about the physical biology and the emotional implications of sex. To Robert Cormier who in books from The Chocolate War, After the First Death and We All Fall Down was never afraid to write about frightening difficult subjects. To Laurie Halse Anderson, author of Speak, who said in an interview: “But censoring books that deal with difficult, adolescent issues does not protect anybody. Quite the opposite. It leaves kids in the darkness and makes them vulnerable. Censorship is the child of fear and the father of ignorance. Our children cannot afford to have the truth of the world withheld from them.”

To all the authors who speak out about uncomfortable truths, I salute you. Keep writing and keep fighting for these important books.

Roleplaying games (RPGs) are one of the most popular ways to experiment with your own stories. Unlike most computer games they are designed to be customisable. You can choose your character, your race, your skills, your weapons and your future. Playing in a group of people with a games master (GM) your characters explore a fantasy world.

Roleplaying games (RPGs) are one of the most popular ways to experiment with your own stories. Unlike most computer games they are designed to be customisable. You can choose your character, your race, your skills, your weapons and your future. Playing in a group of people with a games master (GM) your characters explore a fantasy world.  That’s how it is, for sure. But it’s not how things should be. If toughness is the province of one gender and sexiness the other everyone is impoverished. Imagine if the boot was on the other foot. What if the women got the armour and the men the armour: could Batman take himself seriously in the outfit Fernacular has sketched? (See more reimaginings here)

That’s how it is, for sure. But it’s not how things should be. If toughness is the province of one gender and sexiness the other everyone is impoverished. Imagine if the boot was on the other foot. What if the women got the armour and the men the armour: could Batman take himself seriously in the outfit Fernacular has sketched? (See more reimaginings here)